I’m a health coach with an interest in weight loss and I make a bold statement on my website: weight loss without hunger. I thought it only fair that I explain.

When I first started eating low carb eight years ago, one of the first things I noticed was being released from the tyranny of hunger. I know that sounds melodramatic, but that’s the phrase I used at the time. It was such a relief not to be hungry a couple of hours after a meal. I’ve heard so many other people mention this since and it’s well-documented in research papers investigating low carb and ketogenic diets.1-4 In post-event feedback from the low carb programmes I coordinated last year, 67% of participants said they’d lost weight without hunger, and 24% said hunger was reduced.5

There’s a lot of discussion about low carb and keto eating around whether it works, and whether it is healthy and safe. Done properly, it’s all of those things, but it might not be everyone’s cup of tea. Also, anyone on medication, particularly for type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure for example, should consult their GP before starting because improvements can be dramatic and rapid and medication adjustment might be needed – but that’s a good problem to have, right?6 7 But at the simplest level – which I’ll explain – it’s just good nutritional sense.

Most of all, I think anyone wanting to lose weight deserves to know that if they try low carb eating, they’re likely to be free of hunger. Hunger’s not the only factor, of course, but it’s an important one, because fear of hunger is a barrier to weight loss.8-10

There’s no one definition of ‘low carb’ and it can take a bit of experimentation to work out what suits you. I introduce it in this YouTube video. But typically, you can look forward to weight loss with no calorie restriction and feeling better than you’ve felt in ages. Many are also seeing improvements in a range of conditions from mental wellbeing5 and high blood pressure,11 to fertility issues12 13 and type 2 diabetes.11

So where’s the catch? Well, it’s true that low carb eating means some changes which might challenge your perceptions around food and health. But before we examine what those might be, let’s reframe it all into something really positive.

Another way of describing ‘low carb’ eating is ‘real food’ eating. With low carb/real food eating, you can enjoy a cornucopia of real foods including meat (if you like it, including red meat), fish – especially oily fish, full fat dairy like cheese, butter, cream and yoghurt, bacon, nuts and seeds, and loads of non-starchy veg. You can say hello to bacon and eggs, strawberries and cream, butter on your veg and not having to cut the fat or skin off your meat or fish.

What are real foods? Foods you’d recognise as being as close as possible to their original state. So, fish not fish fingers; corn on the cob, not cornflakes; a block of cheddar, not an individually-wrapped processed cheese triangle in a box. Food that probably doesn’t come in an attention-grabbing packet, food your granny would recognise, products with five or fewer ingredients, say. Compare a home made loaf made from flour, yeast, salt and water, with a sliced granary loaf from a familiar ‘traditional’ brand which contains 20.

Real foods supply a rich diversity of nutrients and fibre that the human body recognises and works with easily to support the immune system, gut health, mental health. So real food supplies all the nutritional ingredients that give our bodies a good chance of working like the efficient machines they strive to be. For many people, just doing this might be enough to help them lose weight or just feel better, more energetic.

The key here is that by focusing on real foods, we automatically avoid sugar and processed foods, and it’s the first step on a low carb journey. In fact whichever dietary approach you choose to lose weight, improve health or save the planet – be that vegan, omnivore or somewhere in between, high carb, low carb or low fat – cutting out sugar and processed foods is top of the list. That’s not disputed by anyone. Cutting out sugar and processed foods automatically reduces your carb intake and is probably a good move for most of us.

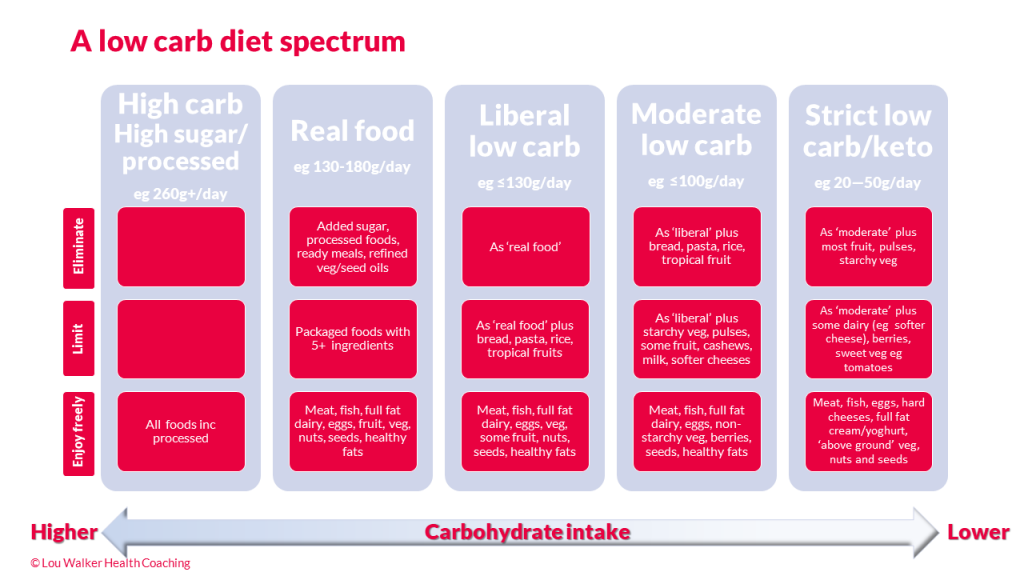

We know about sugar – it’s in your tea, in cakes and pastries, confectionery and jam. White, brown, demerera, honey, agave syrup, it’s all sugar. But did you know that 70% of processed foods also contain added sugar or starch – even some of the savoury ones? Successful low carbers also steer clear of starchy foods. Starch is chains of sugar molecules joined together which get broken down into sugar during digestion. Starchy foods include pasta, bread, anything with flour in it and breakfast cereals… and real foods like potatoes, sweet potatoes and rice. To what extent it’s useful to cut down on real food starches depends on your health, goals and preferences. Figure 1 shows how low carb eating exists on a spectrum and can be adapted to suit you individually. Click here for a larger scale version of Figure 1.

If you’re trying to lose weight, you might also find it useful to avoid fruit. Fruit contains sugar, especially the tropical ones like bananas and mangoes, and grapes. Most berries however, although they taste sweet, actually don’t contain much sugar so can be a good option. The concept of ‘fruit sugar’ or ‘healthy sugar’ isn’t useful because your body can’t tell and doesn’t care whether a molecule of sugar came from an apple or a doughnut. If we’re eating a good mix of veg, we’re getting plenty of plant-based nutrients without the sugar hit.

So, we have lower carb eating if we focus on real food, and avoid sugar and processed food. We have the option to go even lower carb by also cutting down on starchy food and veg, like pasta, bread, pastry, rice and potatoes, and fruit. This is the basic approach which has helped so many lose weight and even put their type 2 diabetes into remission.11 It does mean cooking from scratch more so you don’t rely on takeaways or something out of a packet. But it also means you’re not just being fed, you’re being nourished in a way that improves health and wellbeing in body and mind.

How does low carb eating reduce hunger? Several mechanisms could contribute.

- Real food contains a high proportion of healthy fats and adequate protein (not high protein) which together are naturally filling. When we’ve eaten enough to supply us for the next few hours an efficient set of hormonal mechanisms respond to the protein and fat in our meal and signals to us to stop eating. In effect we have off switches for fat and protein consumption.

- We have no ‘off switch’ for carbohydrate, so avoiding it helps us control our carb intake. The lack of carb off switch is probably an evolutionary hangover. When we were evolving over the last 200,000 years or so, carbohydrate-rich foods were scarce but useful because they probably helped us put on a bit of fat to help us through times of famine. Humans are particularly good at spotting sweet food, too, perhaps for the same reason. If we’re about to go into winter, it’s useful to be able to find berries and honey so we can gorge while we can and get a bit fatter to help us through the lean times.14 From an evolutionary perspective, having no off switch for carbohydrate has probably been very important, but these days, food is not scarce, especially carbohydrate … but we still have the same urges to eat it. It’s why, even if we’re completely satisfied after a main course, there’s always room for pudding or a snack.

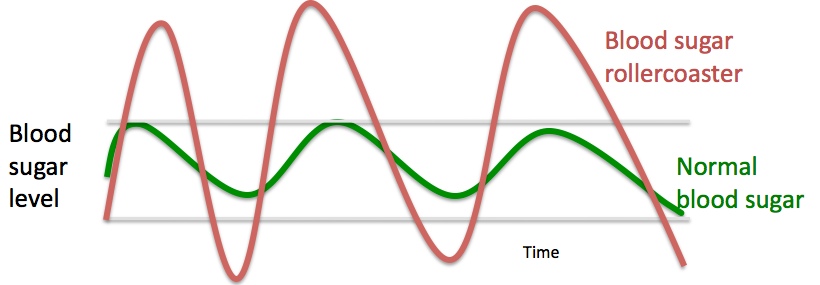

- Low carb eating gets us off the blood sugar roller coaster. A lot of biochemistry occursto keep our blood sugar within quite a narrow range – equating to around a teaspoon of sugar for a healthy adult (not much, is it?!). When we eat, our blood sugar rises and in response, the hormone insulin is almost immediately secreted to remove any sugar in excess of that narrow range. Although protein stimulates an insulin response, it’s tame compared to carbohydrate which sends our insulin levels rocketing, and rapidly. If all is working well, a rapid insulin response to a carby meal will get blood glucose back down to safe levels quickly. But the response can get over enthusiastic, especially with meals containing lots of sugar and little fibre, and drop our blood glucose too low (see figure 2). This can make us feel hungry again with an urgent need to boost blood sugar. The problem is, the cycle can repeat with the cake or chocolate we eat for our urgent sugar fix sending our blood sugar levels up again, with another insulin response to bring it crashing back down. Remember, a ‘normal’ blood glucose reading equates to only around a teaspoon in the blood so a biscuit might easily send it over the top. This blood sugar roller coaster can make us hungry – and it’s exhausting for body and mind. If we eat fewer starchy carbohydrates and sugar, we don’t get such extreme insulin spikes so we don’t get the extreme blood sugar dips and accompanying hunger (the green line below).

- Low carb eating helps to stabilise blood sugar. The opposite of the roller coaster! Our bodies are flexible and can use a variety of fuels for energy including glucose (which is what we’re talking about when we talk about blood sugar) and fat, and can switch between fuels when necessary. If carbohydrate is our main fuel because we eat a lot of it, our metabolic machinery is more geared up to burn glucose for energy. The problem is, we don’t actually store much carbohydrate in our bodies – a total of around 500g in a 70kg adult which would be enough for a marathon runner to last for about two/two and a half hours. If we run out, we can switch fuels to burn fat, but it’s not instant and in the meantime you get urgently hungry. In a dramatic illustration of this, marathoners hit the wall is when their supplies of ready sugar have run out. By contrast, if you’re mainly using fats for fuel, which would happen if you are a low carb eater, your body’s machinery is geared to that and even the slimmest person has many hours’-worth of fat to burn, so there’s always plenty of energy available and hunger is less likely or ‘urgent’. The whole topic is much more complex than this but in essence, low carb eating keeps us metabolically flexible so we have a steady supply of energy, and less hunger.

- Low carb eating gives us easier access to our fat stores to use for energy and therefore prevents hunger.15 Insulin is a fat storage hormone. If we’ve eaten a meal with carbohydrate, insulin enables excess glucose to leave the blood and enter tissues to be used for energy. But if our tissues don’t need any more glucose, it’s eventually turned into fat and stored. This fat storage action is a one-way street. While insulin levels are high (because of a carby/sugary meal or snack), fat is locked away in our fat stores and can only go in. Fat can’t come out. In fact one theory of obesity posits that if insulin levels are high and sugar hoovered efficiently out of our blood and locked away as fat, this would leave susceptible people feeling hungry, despite having adequate fat stores. In contrast, if insulin levels stay low through low carb eating, stored fat is easily mobilised if it’s needed so hunger (which is a signal to us to eat) is less likely.15 Gary Taubes’ new book The Case for Keto explores this in depth.

- Real foods are what nutritionists and dieticians call ‘nutrient-dense’ ie a high proportion of nutrition for a given amount of volume of food. With high carb foods like pasta or white rice you get a lot of energy, but compared to real foods, not a lot of nutrients. Sugar provides nothing but energy (calories) and no nutritients at all. So if you miss out on starch and sugar, you’re not missing out on nutrition if you eat a varied real food diet. (Contrary to popular belief, we don’t need to eat carbohydrate for energy. Our body uses glucose for energy but because our body can make glucose, we don’t need to eat it.16 In contrast, there are some amino amino acids (building blocks of protein) and fats we do need to eat because our body cannot make them. These are called ‘essential’ amino acids and ‘essential’ fatty acids. There are no essential carbohydrates.)

So maybe a combination of some or all these mechanisms combines to make hunger, the drive to eat, less urgent. If we want to lose weight, as long as we eat enough nutrient-dense real food (including healthy fat), the body will be nourished, with a ready supply of energy from our fat stores. And therefore, weight loss! Hooray!

For many, a low-calorie, low-fat diet leaves us feeling hungry so it’s not surprising dieters are obsessed with food and feel grumpy and deprived. The low-cal/low-fat dieter’s body and brain interpret the diet as a lack of fuel and become fixated on addressing this – through hunger, food obsession, and preserving energy which makes us feel cold and lethargic. Willpower is a limited resource and, unsurprisingly, not always up to the battle of fighting our body’s natural urges to get enough fuel, especially if there’s a lot of weight to lose and you’re looking at feeling hungry and deprived for months. It’s tough for even a few days. Being hungry is torture.

Contrast this to someone who eats low carb. Because of the mechanisms outlined above, the body seems not to perceive a fuel shortage so there’s less hunger and little or no sense of deprivation. The body has enough energy and nutrients and can burn body fat which leads to weight loss.

On top of this, because low carb eating seems to reduce hunger, there is no need to restrict food intake or count calories. Instead, guidance is usually to eat according to appetite. I advise clients to eat if they’re hungry, stop when they’re full, and if they’re not hungry, not to eat (unless they need to to take medications or some other medical reason). All this releases people from hunger and the need to obsess about food and use Titanic amounts of willpower to lose weight.

I’m not saying that weight loss is always straightforward, and feeling hungry isn’t the only reason for eating, especially if excess weight is an issue. But if you are wrestling with eating through stress or boredom, it’s a lot easier if you’re not actually hungry at the time.

I hope this is useful. Even before covid-19 came along being overweight was a problem for two thirds of people in the UK. Now with the links between being overweight and covid complications, it’s even more important. Weight loss isn’t easy, but if we can take hunger out of the picture, it might be a lot easier for many.

If you’d like to know more about how Lou could help you lose weight, visit her website: wwwlouwalker.com.

References

1. Martin CK, Rosenbaum D, Han H, et al. Change in food cravings, food preferences, and appetite during a low-carbohydrate and low-fat diet. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(10):1963-70.

2. Kelly T, Unwin D, Finucane F. Low-Carbohydrate Diets in the Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review from Clinicians Using the Approach in Practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(7):2557.

3. Hu T, Yao L, Reynolds K, et al. The effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26(6):476-88.

4. Adam-Perrot A, Clifton P, Brouns F. Low-carbohydrate diets: nutritional and physiological aspects. Obes Rev 2006;7(1):49-58.

5. Walker L, Smith N, Delon C. Weight loss, hypertension and mental wellbeing improvements during covid-19 with a multicomponent health promotion programme on Zoom: a service evaluation in primary care. IN PRESS. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2021.

6. Unwin DJ, Tobin SD, Murray SW, et al. Substantial and Sustained Improvements in Blood Pressure, Weight and Lipid Profiles from a Carbohydrate Restricted Diet: An Observational Study of Insulin Resistant Patients in Primary Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(15).

7. Murdoch C, Unwin D, Cavan D, et al. Adapting diabetes medication for low carbohydrate management of type 2 diabetes: a practical guide. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69(684):360-61.

8. De Leon A, Roemmich JN, Casperson SL. Identification of Barriers to Adherence to a Weight Loss Diet in Women Using the Nominal Group Technique. Nutrients 2020;12(12).

9. Sharifi N, Mahdavi R, Ebrahimi-Mameghani M. Perceived Barriers to Weight loss Programs for Overweight or Obese Women. Health promotion perspectives 2013;3(1):11-22.

10. Gupta H. Barriers to and Facilitators of Long Term Weight Loss Maintenance in Adult UK People: A Thematic Analysis. Int J Prev Med 2014;5(12):1512-20.

11. Unwin D, Khalid AA, Unwin J, et al. Insights from a general practice service evaluation supporting a lower carbohydrate diet in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes: a secondary analysis of routine clinic data including HbA1c, weight and prescribing over 6 years. BMJ Nutr Prev Health 2020:Published Online First: 2 November 2020. doi:10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000072.

12. McGrice M, Porter J. The Effect of Low Carbohydrate Diets on Fertility Hormones and Outcomes in Overweight and Obese Women: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017;9(3):204.

13. Zhang X, Zheng Y, Guo Y, et al. The Effect of Low Carbohydrate Diet on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Endocrinol 2019;2019:4386401.

14. Stamataki NS, Elliott R, McKie S, et al. Attentional bias to food varies as a function of metabolic state independent of weight status. Appetite 2019;143:104388.

15. Ludwig DS, Ebbeling CB. The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity: Beyond “Calories In, Calories Out”. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(8):1098-103.

16. Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care 2019;42(5):731-54.